Aurelio Pontarelli – A Eulogy

In the spring of 1954, on a designated weekend, families across America took their young children to the local elementary school for a very special event. Standing in line by the scores, when each child reached the table up front, they faced a nurse wearing a starched white uniform and nurse’s cap. She took an eyedropper and squirted a couple drops of pink liquid onto a sugar cube, then placed it into the child’s mouth. As Mary Poppins would later sing, it did help the medicine go down.

It was the Salk vaccine, a gift from Dr. Jonas Salk to tens of millions around the world. It would protect all those who took it against ever getting polio, a dreaded disease causing paralysis in the legs of small children. Its protection rate was more than 99%—if you took the medicine.

There could be many reasons why at least one family missed the appointment on that fateful day and did not bring their child to the local elementary school. There would be consequences they could not have imagined.

* * *

In 1964, I was 16-years-old and had been in the Boy Scouts for several years, earning the coveted rank of Eagle Scout. I wanted to go further in scouting but, as an inner-city boy, I could ill afford to do much traveling far from home.

Then the opportunity arose to attend the Jamboree at Valley Forge, about 25 miles west of Philadelphia. Thousands of scouts from around the country, and the world, would set up a massive encampment in a place so important to our nation’s birth. My fellow scouts in our troop were not in a position to go, yet I didn’t want that to hold me back.

I spoke with my parents, then my Scoutmaster, and learned the Philadelphia Council was organizing troops with a mix of boys from many different troops all around the city. Surely, they all had the same idea I did. This was great!

A few weeks later, we met at a large social hall, 35 boys, a scoutmaster and his assistant. We were divided into eight-per-patrol units. As one of the older boys, I was named the Senior Patrol Leader. We were certainly an interesting group, and everyone enjoyed making so many new friends. Then my eyes fell upon Aurelio Pontarelli, who I would come to know as “Ponch” for the rest of my life. He, Jack Snite, and I, would be tentmates—the boy-leaders in the troop.

Our scoutmaster had served as a U.S. Marine in Korea where he lost his right eye, later replaced with one made of glass. He was big and a tough character, authoritative, and very deserving of every ounce of respect we showed him. He was up to the task of organizing and leading such a diverse and gangly set of youngsters.

As it turned out, the boy whose family had not made it on the day they administered the Salk vaccine, a dozen years before, was to be part of our Jamboree troop. Aurelio Pontarelli was one of the fewer than 1% who were stricken with poliomyelitis.

Ponch was not as tall as he would have been without polio, but height was never an issue for him. He had more hard knocks in his life than most would ever know. But none of this was easy to see, because his personality exuded something most extraordinary. He was who he was, had accepted it and, essentially, moved on. If you couldn’t deal with it, it was your tough luck, because he was going ahead to do whatever he wanted—polio, crutches, and the whole disability thing be damned!

More than 95% of the scouts in Philly could not afford to attend a National Jamboree at Valley Forge, or have the gumption to figure a way they could. Not a problem for Ponch. Here he was, in the midst of a large room of Boy Scouts running around and making preparations for the week-long encampment.

Ponch didn’t use a wheelchair, but had two wooden crutches. They had handholds at the height of his hips, and rubber tips on the bottoms. The tops had thick, black leather bands, through which he slid his arms and grabbed the dowel pins, mid-crutch. His arms seemed to waggle in the leather loops a few inches above his elbows. The strength he needed, just to be mobile, was something most arm-wrestling competitors could only dream about.

Something I learned early on was if someone did something Ponch didn’t like, especially if the boy was a smartass to another scout, and, worse still, to Ponch, he would take a swipe at the offender’s shins with the wooden weapons he carried with him wherever he went. It only took a couple of smacks, which could be heard from a good distance away, followed by a cry of pain and remorse, for anyone nearby to realize—don’t mess with Ponch. But he was always good natured and it was more often the threat of a shin-slap which tamed the misbehaving youths around him. I was glad to have him as my partner in leading the young boys.

At any large event with scouts, near or far, there are always gatherings of boys sitting in a circle around a blanket strewn with Boy Scout-related paraphernalia they are eager to trade. The neckerchief, a standard part of the uniform, is a square of cloth, folded in half to form a triangle, then put around the neck and held together in the front by a slide. There were standard neckerchief slides, but also the option for a myriad of styles and designs, only limited by the wearer’s creativity. All of the twelve regions of scouting across the country had their own specific neckerchief slides, which were top priorities and coveted in the trading scrum. Other items, like patches worn on the shoulders or pocket covers, were also traded. But scoring a full set of region slides was the goal. It was classic Boy Scout stuff to enjoy and remember for years to come.

My father had been from the Great Depression generation where whittling was a pastime for every boy with a penknife and a piece of wood. He wanted to enhance my ability to make trades by having something interesting to offer. At home, he took out his penknife and grabbed a couple of old broom sticks. We sawed them off in five-inch lengths and dad began to whittle. Within a few minutes, he produced the basics of an Indian totem pole, with four distinctive faces. He drilled a hole in the top face to insert a large hooked nose. I did the painting, white, with primary colors for the details of eyes, nose and mouth. A few old leather shoes contributed their long tongues, each cut to become a loop on the back and screwed into the wood for the neckerchiefs to slide through. After a few days of work and painting, we had two-dozen of them, ready for trading at Valley Forge.

I shared the totem pole slides with Ponch and Jack, and we participated in trades in many circles of boys sitting around spread-out blankets covered with goodies-for-trade. It was exactly what you wanted when 50,000 boys from far and wide got together in fun and good spirit.

One night in our tent, Ponch said we should create something new for a neckerchief slide, as we were running out of the totem poles. He opened a single-portion box of Rice Krispies. As he began to eat them, an idea popped into his head. He suddenly grabbed his knapsack and pulled out a sewing kit, withdrawing a needle and thread. It wasn’t clear what he had in mind, but his developing idea became obvious in a few minutes.

The Lenni Lenape tribe had lived in the Philadelphia area for centuries. We were all familiar with their history and some of their jewelry. Ponch began to stick the threaded needle through individual pieces of the Rice Krispies until he had a couple of inches linked together. He turned it into a loop and held up his circle of cereal and pondered.

Jack and I were in with him right away. We began to thread needles and created more loops, but somehow it just wasn’t enough. We made double loops, sewn together, and had two-inch trails of “beads” hanging down.

After more experimentation, Ponch held up what he saw as his masterpiece—three loops at the top, and different lengths hanging down from it. He grabbed his neckerchief and put it on, then slipped his new creation up into place. While it was a little flimsy, once in place, it stayed and did the trick. But who would trade for such a thing?

Ponch said we had to have a name for the slide and were hard put to think of anything. We went back to the Lenni Lenape idea and Ponch suggested it be connected to them, even though the Indians from more than a hundred years ago did not have Rice Krispies. But it didn’t matter to Ponch. He liked the idea of them being rare and precious from days-gone-by, but we needed more.

We were thinking of words from the old times, like a whippoorwill. Instead, I suggested the “creator” of the slide should be honored. In a few minutes, we decided on Crutch-a-Whippie! This would be the decoration we would wear, and we made more of them. It didn’t take long to realize they were fragile and had to be handled with care, but they hung from the neckerchiefs just fine.

Only a few years before, Joseph Heller’s book, Catch-22, had come out and was the most popular read in America. From this came our rationalization to make the Crutch-a-Whippie a valuable product. How would that work?

If you questioned the validity of the neckerchief slide and tried to crush it, if it didn’t crush, then it was from more recent times and was not “real,” that is, not from ancient times. But if it did crush under pressure, it meant it was real. But then you had a small pile of dust in your hand. The bottom line was, don’t crush them, because if you do, you will have destroyed an ancient relic!

This was our version of a Catch-22, when it came to our new creation of the Boy Scout neckerchief slide. The next day we put it to the test.

In a scrum of traders, Ponch sat down near the middle, wearing one. He held up a couple more of our Crutch-a-Whippie neckerchief slides and told the story about them. Fortunately, we were from Philadelphia, where the Lenni Lenape Indians had lived, adding credibility to what he said.

In no time, boys were offering up their own neckerchief slides, some region slides, but also patches and badges from across the country.

Through most of that night we produced more Crutch-a-Whippie neckerchief slides for the next day of trading. Each time, the boys were told of the Catch-22 story, so they handled them with care.

Of course, we were doing this all in good fun, and anyone—especially a parent or Boy Scout leader—could tell exactly what the slides were made of. But they saw them as interesting souvenirs from a wonderful week the boys would tell their children about.

It is hard to think back, now sixty-years ago, and recall Ponch and his Crutch-a-Whippie neckerchief slides, and not have a big smile come to my face.

All three of us—Jack, Ponch, and me—had been in choirs, both school and church. At the time, just as the Beatles were beginning to take over the airwaves, the old 1950s groups were still our favorites. Lee Andrews and the Hearts sang Tear Drops, from 1958, which was worth humming all day. We all knew the words and started singing it a cappella. The funny thing was, we weren’t bad as a trio. I sang lead, and Ponch filled in the bass notes. Our harmony was passable.

Jack had recently broken up with his girlfriend and wanted to do something special for her. A few weeks after the Jamboree, we met at his house where he had a tape recorder. (Not everyone had one, and this was 30-years before cell phones.) We listened to ourselves, and after a few tries, it did sound pretty good.

The lyrics say the singer had run out on his girl and was hoping to get her back—which was exactly what Jack had done and wanted to fix—with this song for her. Ponch and I were willing to help, so we crooned our best. Likely, the recording is no longer around, but the original version of the hit song is on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taBMfRd_RQA

Picture three teenagers from Philly finding a corner of a school corridor to listen to our harmony in the echoes, and that was us. What a threesome! (We toyed with the idea of calling ourselves The Crutch-a-Whippies, but thought better of it.)

Time passed and we all went to different schools and had different interests. I was a senior at Germantown High, ready to graduate in a few weeks in January 1965. One day I looked down the hallway and saw a group of disabled kids. Ponch was in the middle, leading them. I couldn’t believe it. What were they doing at our school?

It turned out the Widener Memorial School was specifically created for children with disabilities, and had far fewer students than the regular public high schools. To have the full graduation experience with a few hundred students in a class—and because they were closest to Germantown High— they joined us and became part of our graduating class for the ceremony.

I ran toward him and he worked his way to me, faster than I had ever seen him move on crutches before. It was a grand celebration. I introduced him to my classmates, and he did the same with me. The coincidence was astonishing and it meant more time spent with my old Boy Scout pal.

After Germantown, we went to different colleges. I was two-hundred-miles away at Penn State, and we lost track of each other. Without the current-day’s social media and cell phones, it was easy not to know where old friends had gone and what happened to them.

After graduation I went to Villanova Law and was a counselor in Austin Hall, the freshman football scholarship dorm, aka, the Animal House! But it did place me on the main campus, while the law school was across the railroad tracks and up the hill, a good distance away.

One day, walking back to my dorm, I saw a silhouette which could only have been my old friend crutching his way down a path with colleagues on both sides. He was a student at Villanova, which I hadn’t known.

I stopped in the pathway and, as the group approached, I waited patiently. When they were only a few feet away, Ponch looked up. With a straight face, I said, “Excuse me, I’m looking for the ancient Lenni Lenape artifact called a Crutch-a-Whippie, and was wondering if you know where to find one.”

The other guys with Ponch had giant question marks on their faces, but Ponch glided forward and it was, again, a renewed friendship after another four years.

I wanted a break from my hours of legal studies and thought of how much I missed singing in the Penn State Men’s Glee Club. My voice, from a high-school first tenor, had sunk down to a low second bass. Mr. Fisk, the Villanova Singers choirmaster, welcomed me. On the first night of practice, who should be right nearby in the baritone section but—Aurelio Pontarelli! I couldn’t believe it. Almost as soon as we saw each other, and in those surroundings before practice began, I started with, “I sit in my room, looking out at the rain…” and Ponch jumped in, “…my tears are li-ike cr-ys-tals, they cover my window pane….” By this time, the other boys joined in with the harmony.

“I know you’ll never forgive me, dear, for running out on you, (doo-doo-doo-dooo), I was wrong to take a cha-ance with some-bo-dy new…”

It was quite astounding. While our colleagues were laughing and slapping each other on their backs at how great they thought they sounded, Ponch and I were thinking of our days at Valley Forge. In the bigger scheme of things, it hadn’t been too many years, but for teenagers, it seemed like a long time ago and was still something special.

After law school, I went into the FBI and served there for nearly three decades. I was assigned to six different field offices all around the country, a great career, mostly catching spies for a living.

I retired in 2000 and lived with my wife and five children in Miami, now in Fort Lauderdale. I continued to investigate and had an occasional trip back to Philly. In 2016, a case brought me to the City of Brotherly Love. Once I finished all of my interviews and was ready to fly south the next day, I wondered—who might I reach out to before I leave?

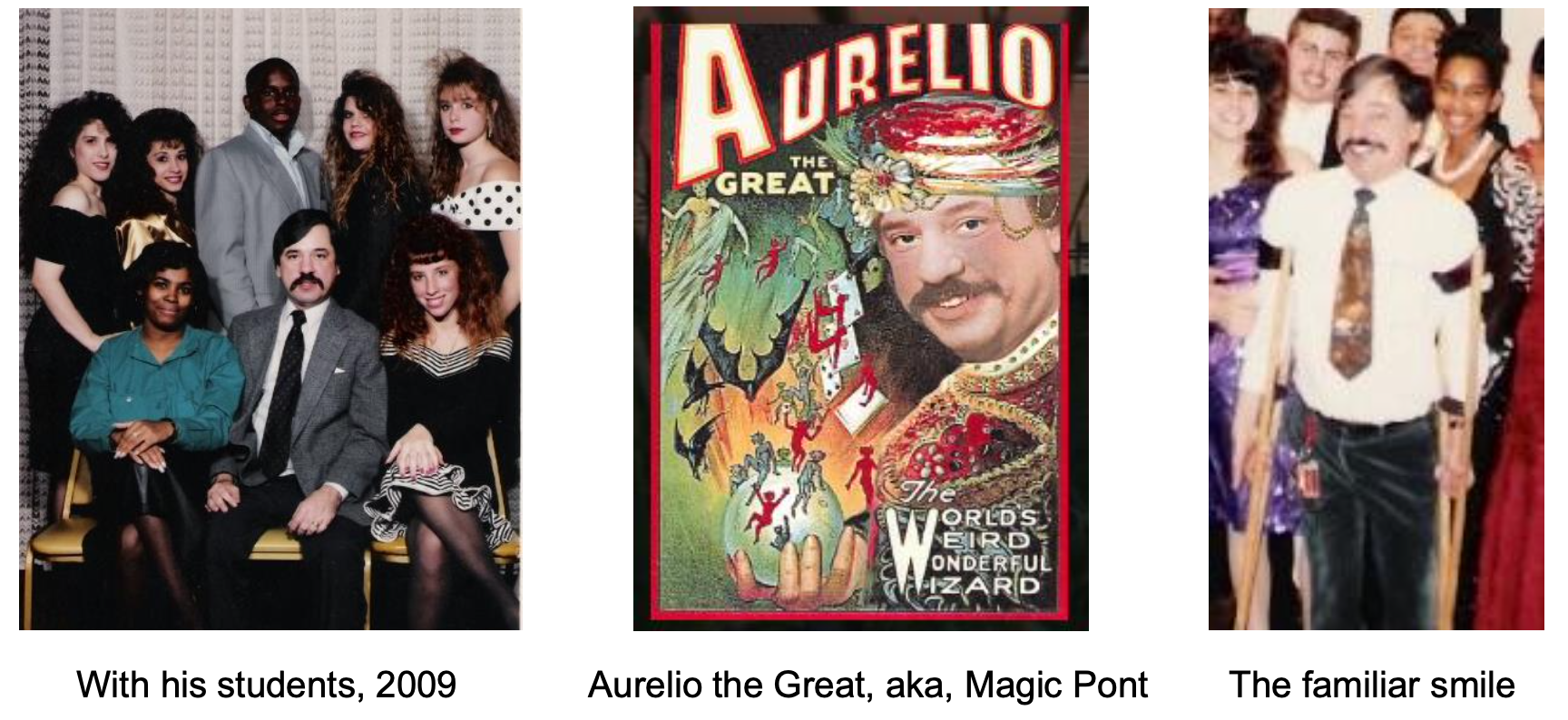

Now, with great databases, I found an address in New Jersey and made a call. Within a couple of hours, I pulled up to the Pontarelli residence. This time, it had been more than half-a-lifetime since we had seen each other and we brotherly-hugged again. I learned all about Ponch’s teaching career and achieving the skill of a master magician. I was grateful for meeting Mary, the love of Ponch’s life, and even to spill the beans to her on some of the shenanigans we used to pull in our younger days. It was a night to remember.

A few years later I received a call from Mary. Ponch had gone into hospice care. Anyone who knew him would truly be saddened. A couple of weeks ago, she called with the not-unexpected news of his passing on April 12th.

I had not known him as the wonderful and award-winning teacher he was, loved by all of his students. While he had done a few magic tricks and sleight-of-hand card play for me at his home a few years before, that was part of his life I had not lived through. But what I did know about him, the man—and yes, “the legend” that was the Aurelio Pontarelli, I wanted to share with anyone who only knew him later on. They missed the part where a young Ponch would whack misbehaving Boy Scouts with his crutch to keep the peace, and had conceived, and artfully carried out, the Crutch-a-Whippie neckerchief slide at the Jamboree in 1964. He had been willing to harmonize with his buddies to get one of their girlfriends back, to the tune of an old ‘50s song, and he even wrote a book which summed up his motto in life, Don’t Ever Say Can’t, and he didn’t.

On my 2016 visit, he learned I had a daughter born with spina bifida, a major disability where a wheelchair would always be nearby. He reached around and pulled a copy of his book off the shelf and signed it to Natalia, with an inspiring message. They would be soulmates after she read only the first few pages, so compelling was the man in his never-ending quest for those around him to do better, be better, improve themselves, and live the best lives they could.

I miss my childhood pal and always try to be that better man. I knew the boy he had been and was proud to see the man he had become. Rest in peace, Aurelio “Ponch” Pontarelli, my old friend….

Wayne A. Barnes

Plantation, FL

May 14, 2024